![]() |

| Panther-spotted Grasshopper (Poecilotettix pantherinus) subsp. santaclausi |

So I wanted to start our new theme with a little bit of holiday cheer (to the

SW Insect facebook group but my Grasshopper Santa looks an awful lot like the Grinch. I wonder: did he inspire Dr. Seuss? Anyway, I’m sure that you all have a cricket chirping in some dark corner, some summer grasshopper photos in the sock drawer – let’s see them! Also, grasshoppers, tree crickets and katydids are actually among the few insects that are still out there right now.

![]() |

| Trimerotropis cyaneipennis |

Mt Lemmon, 8000 feet elev. Pima Co,, AZ, August

Many Bandwing Grasshoppers are very cryptic while they are sitting quietly. When they fly up, many flash colorful hindwings. This certainly is used as a mating display, but I am sure it also causes a startling response in many predators. Of course it is very difficult to photograph this and I am showing a pinned specimen instead. Those underwing colors are usually part of the species description so it is useful to note them down with your observations, even if you can't get a photo

![]() |

| Our 3 Arizona species of Insara: Insara covilleae on Creosote, Insara on Mesquite, Insara tesselata on Juniper |

I am always amazed how many of the caterpillars, stink bugs, beetles, leafhoppers on juniper and mesquite are using a similar shape dissolving technique: they are green with white or silver markings. That coloration hides them amazingly well among those small leaves and leaflets where one would expect to see insects of any color to stand out as big dark blobs

![]() |

| Bootettix argentatus (Creosote Bush Grasshopper) |

Also well hidden by those white markings that look just like the glossy spots of the creosote leaves or the space between the leaves.

Its range is basically the same as Creosote Bush (Larrea) in North America from western Texas and New Mexico to California, and southward. A vegetarian that CAN digest all the toxic ingredients of Creosote might as well be completely specialized on it.

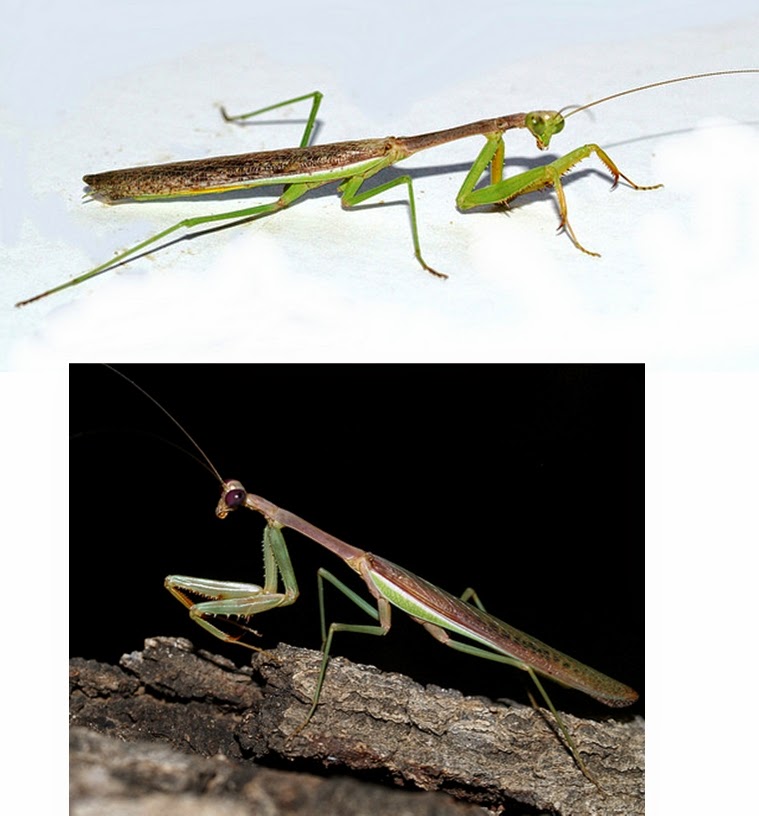

![]() |

Prorocorypha snowi (Snow's toothpick grasshopper)

Montosa Canyon, Santa Cruz County |

Known only from "sky island" mountans west of the Continental Divide in southeastern Arizona and Sonora. It lives in tall bunch grasses in moist pockets in the lower elevations of those mountains There is a similar, not quite as elongate species, Paropomala wyomingensis that occurs more widely. Apparently overwinters as eggs, hatching in spring, with adults in summer and into autumn.

![]() |

| Paratettix aztecus (Aztec Pygmy Grasshopper) Sabino Canyon |

![]() |

| Paratettix mexicanus, Marana |

Close to water I often find the smallest of adult grasshoppers, Pygmy Grasshoppers. The characte r to recognize them by is the very elongated pronotum that is tapered and usually covers abdomen. They overwinter as adults, so you may find them at Sabino Creek on warm winter days. They are extremely variable, but we seem to have just 2 species here in AZ.

![]() |

| Syrbula montezuma (Montezuma's Grasshopper), male |

![]() |

| Syrbula montezuma (Montezuma's Grasshopper),female |

Garden Canyon, Huachuca Mt, Cochise Co, AZ

a species of Slantface Grasshopper,

Southwestern United States: Arizona east to Texas, north to Colorado, and south through much of Mexico. Areas of tall grass in arid grasslands

![]() |

| Melanoplus thomasi (Thomas's Two-striped Grasshopper) |

Not all GHs are cryptic and camouflaged: everybody knows the fantastic Rainbow GH, but even some Spurthroats are amazingly colorful, at least out here, in the Southwest.

M. thomasi can be abundant in late autumn in relatively moist, lush, weedy meadows. Wide spread: Coast to coast across southern Canada and most of the US except Florida, south Atlantic and Gulf coastal plain, and southwestern arid regions. Perhaps into northernmost Sonora and Chihuahua, Mexico.

Melanoplus thomasi in the southwest is usually bright blue-green with brilliant red on inner hind femur and brilliant red hind tibiae. Other populations just yellowish and brown (sometimes greenish or blackish) but always with two distinct pale yellowish stripes along sides of top

![]() |

| Capnobotes fuliginosus (Sooty Longwing) |

![]() |

| Capnobotes fuliginosus (Sooty Longwing) nymph |

Florida Canyon. Santa Rita Mts, Santa Cruz Co, AZ, USA

This is a very big katydid that is more carnivorous than other Orthopterans in AZ. While most of them will add protein to their diet when they can, these big guys are active nightly hunters as even the nymph on the right proves. The adults can bite defensively too and, when threatened, do an impressive startle display with their big dark hind-wings.

![]() |

| Stilpnochlora, azteca or S. thoracica Piotr Naskrecki det. |

an enormous katydid from Sonora Mexico, May 2014, but also found north of the border. It is much larger than our big Anglewings. The spikes along the hind legs could be a formidable defensive weapon

![]() |

| Arethaea gracilipes Thread-legged Katydid |

Canelo Hill, Santa Cruz Co, AZ August

Here is another orthopteran superbly adapted to living in the thin summer grasses. Hiding in plain sight. I have better macro shots, but I like this one because it shows the insect in its 'element'

![]() |

| Gryllus personatus, Badlands Cricket |

These are bigger than most other field crickets I have seen

... Picture Rocks Pima Co, AZ, USADave Ferguson on BugGuide: One of few species usually easily recognized by coloration and pattern. It has a distinctive pattern of dark on tan that varies a bit, but is always basically the same. Individuals may be long-winged or short-winged. They often come to lights, particularly long-winged individuals which can fly. Adults will shed hind wings (not tegmina) when molested, and thus long-winged individuals may become non-winged individuals

The song is a typical Cricket-like chirping, but the frequency and rate of beats make it sound less musical and a bit more "metallic" than most other species of Gryllus.

Habitat :

Mostly open clay, silt, or calcareus areas with light-colored dusty soil. Mostly in desert and dry grassland. Often in "badland" type areas on the Great Plains. They tend to be most often seen living in cracks in the gound, and pouring water into the cracks where you hear them singing is often the easiest way to find them; they often rush out of the cracks.

Season:

Adults are usually seen late spring through summer. Earlier in the south than in the north. Late specimens indicate that there may be a second brood in some regions..

![]() |

Pristoceuthophilus arizonae Ted Cohn det.,

a Camel Cricket from Mt. Graham, AZ |

I know that in many states, especially where there are basements under houses, camel crickets are common and considered undesirable, but here in dry Arizona I see them really rarely and we are usually excited to find one.

Many Orthopterans use songs to claim territories and attract mates. Some are still active at this time of the year. Here is the Christmas song of a Tree Cricket at the Santa Cruz River in Marana

![]() |

| Swaison's Hawks over the grasshopper meadows of Sulfur Springs Valley. Photo Lois Manowitz |

Orthoptera are probably one of the most successful groups of animals in the wide grasslands of Southern Arizona, at least considering the biomass that they produce. So it is not surprising that many reptiles, mammals and birds rely on the abundant supply of nutritious prey. Especially impressive are the huge congregations of migrating birds of prey that can be seen feasting in Sulfur Springs Valley in Autumn.

.jpg)

%2BNymph.jpg)