![]() |

| Solenopsis xyloni (Southern Fire Ant) |

Two days ago we woke up to Fire Ants marching across the kitchen counter (after hummingbird food had been prepared there the evening before). A thorough scrubbing of all surfaces will convince them to stay outside, I hope. No new arrivals for a couple of days at least.

![]() |

| Polymorph workers: many different sizes |

On the brighter side, theses are our little native

Solenopsis xyloni (Southern Fire Ant), not the feared introduced Red Fire Ants,

S. invicta, that I met in Florida on my last night of gator watching that left me literally scared for life.

But our little guys can sting too. When they come to my black light at night to tackle any small scarab that falls and lands on its back, they sometimes also get my toes. They seem to always plan their attacks until several are in position ... just like their bigger relatives in Florida. Their stings burn and itch but are really just a minor irritation. In our kitchen they were so docile that I first doubted my identification. No attempts at stinging at all.

![]() |

| Tackling a Minute Black Scavenger fly |

But outdoors they are voracious and attack insects much larger than their size and manage to subdue them. So I assume that the crack in the kitchen wall (?) that they must have found is now free and clean of any other bugs. OK. Just stay off my counter and the floor!

![]() |

| Southern Fire Ants in the compost bin |

Outdoors, I have noticed a belligerent colony close to the compost bin. We have lots of space, so this is far from the house.

![]() |

| Southern Fire Ant on a barrel cactus fruit |

Solenopsis xyloni are also usually found on barrel cacti. To get the photo for this blog I just pulled a fruit from a barrel in the front yard and immediately had a couple of volunteers. I knew this would be the case because I'd seen the ants on barrels even in winter when I was looking for nymphs of leaf-footed bugs that develop on cacti.

At this time of the year saguaro cacti drop their fruit. Birds have been feasting on the sweet seed pulp before the fruit falls, but there should still be enough left to make some ants happy. Under a free standing saguaro, I found some of those fresh bright-red stars. There were some very small extremely fast-running ants, a

Pheidole species I believe, but no Fire Ants. Do they not like saguaro fruit? Or are their colonies simply too far from this cactus?

![]() |

| At nigh at my black light site: Southern Fire Ants taking apart a scarab beetle and gorging on sweet saguaro pulp |

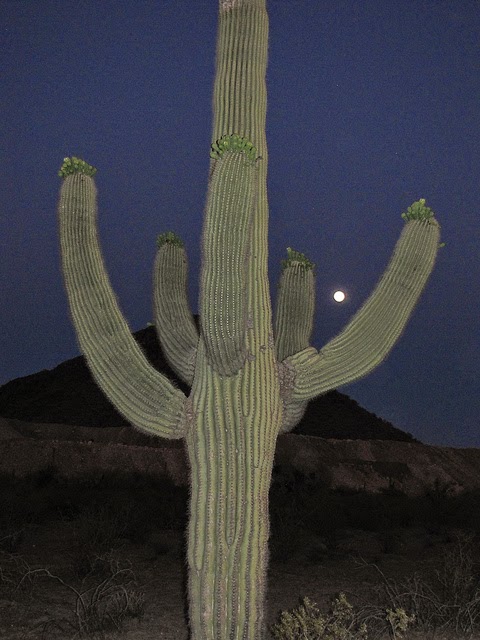

To test my theory I moved a few of the fruits to my black lighting site because I know that

Solenopsis xyloni lives around there. I turned on my lights for some hours after sunset (a gorgeous one with virga, rainbow, red clouds and early moonrise).

When I returned the Fire Ants had performed to expectations: not only did they overpower a small scarab beetle (

Acoma sp.) and were just testing the resilience of a much larger

Oxygrylius, they were also all over my saguaro offering.

I know that the time of day and temperatures also play an important role in an ant's activity, but I did find

Solenopsis xyloni active in the afternoon on the barrels but not the saguaro. Since they obviously love the saguaro fruit, I am back to my idea that there simply is no colony close to the free-standing saguaro. Why?

The areas around the barrels and the columnar giant looks quite similar to human perception. So is it the cacti themselves that make the difference? Their yearly cycles are quite different. The saguaro blooms in April/May, and has fruit in June. As far as I can tell, those are the only times when saguaros have anything to offer to ants.

![]() |

| Barrel Cactus, this year's flowers and buds surrounded by last year's fruit |

By contrast, the thick-walled fruits of the barrel stay on the plant, often for years, so several 'generations' of fruit are constantly present, arranged in rings around the center that keeps producing new flowers once a year, in July/August. Eventually the fruit are chewed open by rodents and the seeds disappear.

Barrel cacti also offer sweet sap from extra-floral nectaries all year round. It could be that the barrel cacti (via coevolution) are 'making sure' that ants have a reason to hang around. The cacti may be employing armies of little fighters for its protection against other bugs and the distribution of its seeds by offering them sweets. I have seen the ants attack cactus-juice-sucking coreid nymphs in several cases. The little Fire Ants also like the sweet stuff around the barrel cactus seeds, but I think distribution of those seeds may fall to some larger ant species that can carry more weight.

![]() |

| A jumping spider killing a coreid nymph on a barrel cactus |

It is possible that barrel cacti rely overall more on arthropods as allies than saguaros do. Saguaros have many avian house guests that nest in or on the cactus or feed on nectar and fruit pulp. Many of them are insectivore gleaners like cactus wrens that also peck many insects off their host's thick skin.

Barrels are very vulnerable to rodents so they are tightly covered by a mail of interlocking thorns. This formidable defense may keep many birds from spending too much time on a barrel, and at any rate barrels are not tall enough to provide protective spaces for nests. Ants and spiders however have the ideal size and agility to police that space under thorns and between ribs.

Both saguaro and barrel cacti eke out a living in spartan surroundings. There is not much more than sand, widely spaced creosote bushes and cholla cacti. Under these borderline conditions the reliable yearlong provider may win out over the once-in-a-year party host when the opportunistic Fire Ants are choosing a neighborhood to live in.

![]() |

| Pheidole sp. left and Messor pergandei right. Colonies close to the saguaro |

I am not saying that the saguaro neighborhood lacks ants: besides the

Pheidole colonies, there is a huge permanent

Messor pergandei colony. But those ants have a completely different social, foraging and storage system than the Fire Ants.

With this blog, I would like to stress that not all ants are alike, every species has its own ecological niche, and not even all Fire Ants are alike. The imported, highly invasive Red Fire Ants are established all the way from Florida into Texas in the east and in California in the west. But they need more moisture than they would find in southern Arizona and they may be too frost sensitive to live on the Colorado Plateau in the north. So they may never overrun Arizona.

Living with ants (and you will, if you live in Arizona) is easier and far more interesting if you learn about the different types, one species at a time. Theirs is a densely populated and highly socially organized world to discover.

Please do not contact me about methods 'to get rid of ants'. I have no experience in that field and - beyond my own kitchen counter - no interest in gaining any.