![]() |

| Dynastes granti, male |

Early this summer two little boys from New York were all set to hunt for charismatic, big beetles in the forests of Japan. But due to a terrible political decision, radioactive material from the

Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster had been spread to the area of the beetle camp that they were planning to attend, and they had to cancel their trip. So their mother contacted me through Eric Eaton, and I got to organize a 'Dynastes granti Quest' in Arizona for them.

Last Sunday, I picked up the two boys and their mother at the Arizona Desert Museum where they had attended the Rattlesnake and Gila Monster presentation. The whole little group was delightful. So full of enthusiasm and energy!

Dynastes beetles occur in the mountains around Tucson, but they are not very common. Since I had to be sure to find at least a couple for each boy, we headed north to the Colorado Plateau. A long drive that showed off some of Arizona's best landscape types.

Still close to Tucson, we crossed some beautiful desert, studded with chollas and saguaros, but I noticed that this wasn't quite the typical desert the kids had expected: It was much too lush and green.

Driving north on Highway 77 we were soon gained elevation, passing an old copper mine, then following the San Pedro River to its confluence with the Gila River - all great habitat for Dynastes with lots of ash, cottonwood, sycamore and oak, but rather inaccessible.

So we went further north through Globe and crossed the dramatic Salt River Canyon, where everyone who wasn't too deeply asleep got to stare down into the gorge. Storm clouds were piling up and it had began to drizzle. I was getting little worried...

![]() |

| Salt River Canyon |

North of Salt River Canyon reddish rocks beautifully set off the abundance of road-side sunflowers and the fresh green of trees and bushes along creeks spilling down from the mountains. In good monsoon years like this one, we really get a second spring in August. No photo ops now, we were pressing on to our destination, a prosaic little gas station in the middle of nowhere. But that's the point: the gas station lights are the only ones as far as the eye can see and they attract the beetles without any competition from street lights or houses. Also, the station is private property and the owners are friendly enough with us weird bug lovers to allow us to collect. The customers, all Apaches, some of them tribal policemen, were amused, but interested. There were friendly greetings from everyone and lots of tips where else we could find the big, grey-green beetles.

![]()

In a meadow across the street, under an illuminated casino sign, the kids found grasshoppers and lots of beetle wings and heads. I noticed Javelina scat full of exoskeleton pieces. Two Apache ladies stopped to tell us that a mountain lion had been seen there for several nights.

![]() |

| Javelina and Mountain Lion. Included for my New York visitors who didn't get to see either |

I figured the food chain like this: huge beetles and moths dropping down from the lights of the sign, javelinas coming to feast on them, and a mountain lion stalking the javelinas. Ok, kids, stay close!

Soon Mom found the first big female Dynastes granti hiding in the ashtray of the gas station. Did I call our hunting ground prosaic? Two boys plus one beetle equals a fight.

Luckily lots of Rhinoceros Beetles started to literally fall out of the sky right around sunset. The bigger Dynastes took their time, but eventually we got them too, plus a few Chrysina gloriosa and a White-lined June Beetle who kept hissing at us. When the gas station closed at 10 pm, we had 10 females Dynastes and a nice major male. We got another female at the little church in Carizzo.

![]() |

| Some of our beetles are well received at the Arizona Desert Museum by keeper Catherine Bartlett |

At home I had another very frisky Dynastes male in reserve, provided by Catherine Bartlett from the Arizona Desert Museum, just in case we wouldn't find any. In return, she got 6 of the females we collected for the ASDM breeding program. Thanks for helping out Cathy!

But back to our trip: After sleeping a few hours in a hotel in Globe, Mom got tied up in a conference-call with her office in New York, and the rest of us spent the morning relaxing in a friendly little park in the historic down town. It's nice and cool in Globe! The boys turned at least one local kid into a bug-lover.

Another long drive took us back to my house in Picture Rocks (NW Tucson) where our beetles were transferred from the camping cooler to the safer refrigerator.

After that, we were on the road again. This may seem like an awful lot of driving and we did get to hear the proverbial 'Are we there yet' a couple of times, but with temps hovering above 100 F airconditioned cars are a real haven. Also, we were all turning as night-active as the beetles by now.

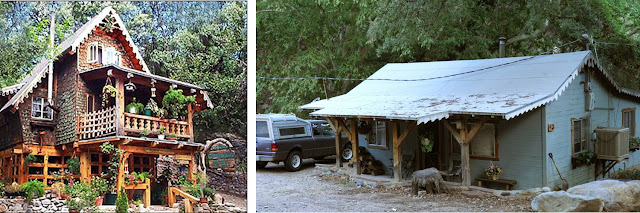

Our next destination: the cute, if overly decorated, KuBo B and B in Madera Canyon. It turned out that we were actually staying in an older cabins accross the street. We really enjoyed it there: the little patio directly overlooks Madera Creek which was running.

What a great place for New York kids to explore! The boys, 5 and 7 years old, impressed me with their sure-footedness and athleticism. The kids' mother was absolutely great with her perfect mixture of letting them go (jump the creek, climb the steep banks, throw huge rocks), and still always being right there to the rescue if necessary. The hours at the creek were definitely a high point of the trip.

At night we had my mercury vapor / black light set-up right in front of the cabin. Just before we arrived, two big storms had cooled the air in Madera Canyon so much that for hours not many moths or beetles appeared. So we spent time in the cabin, snacked on the provided bananas and apples, and studied Eric Eaton's 'Field Guide to Insects of North America '...

![]() |

| Watching a huge at-faced Orb Weaver Spider |

![]() |

| Chrysina gloriosa |

![]() |

| Chrysina beyeri photo by Laurent Lecerf |

Around 10pm the temperature began to rise again and we finally got to see several of the charming big Chrysina beyeri that kids always love. In the end I was the only one a little disappointed with the black lighting results. Everyone else seemed impressed and delighted. I wished they could have seen the black lights on a warmer night in July.

Tuesday morning after packing we hit the gift shop of the Santa Rita Lodge. Lots of nature books went home with the kids. We learned that all summer long a bear had used a well at 'our cabin' as a place to find water before the creek started running a couple of weeks ago (that's very late, because we are still in a drought, even after our latest monsoon storms).

In the grassland of lower Madera Canyon, we found Horse Lubbers, Giant Mesquite Bugs, Big Long-horn Beetles on Baccharis, mating buprestids, Flannel Moth caterpillars on Mimosas, and hundreds of puddeling butterflies. Even though the 5 year old was nearly falling asleep on his feet, we had a hard time tearing ourselves away for the ride home. Well, home for me, for my new friends just another stop on the way to the airport and the flight back to New York.

![]() |

| Safely in New York enjoying Japanese beetle food |

I shipped the beetles over night by fedex, as the airline did not allow to bring them on board. All the bugs got to New York alive and immediately took to the specially imported Japanese Beetle Jelly. The White-lined June Bug began to lay eggs an hour and a half after she landed on the NY doorstep and hopefully the Dynastes beetles will soon follow suit.

Here's one of the emails I received on Thursday:

Margarethe, thank you so much your kindness.

Kids said"Arizona trip was a best in the world!!!!"

It was a great experience for us.

They won't forget it forever!

They already ask me to stay longer in Arizona next year.

Beetles are very well and seems very happy.